Comparison of HSE ACOP L8 and HSG 274 guidance with previous versions of the ACOP

This is a longer version of BSRIA article, ‘HSG 274 Legionnaires' disease, Technical guidance’ published in April 2015. It was written by Reginald Brown, Head of Energy & Environment, BSRIA Sustainable Construction Group.

Contents |

[edit] The Approved Code of Practice

The original Approved Code of Practice for Legionnaires disease was published in 1991, but the document which people are most familiar with is the ‘Approved code of practice and guidance’ that was published as L8 in 2000. Part 1 of that document is the approved code of practice (ACOP) which deals with the identification and management of the risk of Legionnaires disease and Part 2 is the guidance that is split between cooling towers and hot and cold water services.

As a result of public consultations the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) decided to separate the ACOP from the guidance, with the latter being developed by industry groups as HSG 271 Parts 1, 2 and 3. Part 1 is concerned with cooling towers and Part 2 is concerned with hot and cold water services. Part 3 is concerned with “other” systems but is little more than a list of systems that may be encountered, though it does include a recommended inspection frequency.

The original L8 ACOP and guidance contained 61 pages whereas the new set of publications that replace it amount to 158 pages. Most of the increase in bulk has been due to lengthy descriptions of the design and operation of cooling and domestic water systems in HSG 274 Parts 1 and 2. The actual ACOP has hardly changed (apart from the introduction), with most of wording identical to the original.

The changed introduction describes the new structure of the documents emphasises that certain issues now have ACOP status, including:

- risk assessment;

- the specific role of the appointed competent person, known as the ‘responsible person’;

- the control scheme and what it should include;

- review of control measures;

- duties and responsibilities of those involved in the supply of water systems, including suppliers of services, designers, manufacturers, importers, suppliers and installers of water systems.

However, if you were complying with the intent of the ACOP before 2013, you will almost certainly be compliant now.

One new feature is that the ACOP identifies examples of low risk situations that ‘do not require elaborate control measures’ e.g. buildings without water storage. There is also a desire to simplify the bureaucracy for very small businesses i.e. those with 5 or less employees (para 70). Legionella risk assessment has undoubtedly been a growth industry where some providers have possibly overstated the complexity and costs of their services.

There are some more subtle changes of emphasis such as in para 52. The new guidance emphasises the need to provide information and training to all staff that might influence the risk exposure. Previously it was only those appointed to carry out control measures.

Some of the key requirements for the design, installation and commissioning of systems are now clearly part of the ACOP whereas they were previously categorised as guidance. This may make it easier for HSE to prosecute system designers and others in the event of an outbreak.

[edit] Guidance on evaporative cooling systems

The previous guidance contained a basic description of the different types of cooling towers followed by a brief section on management, treatment and monitoring. This is replaced by HSG 274 Part 1, which contains an extensive chapter of 'Requirements of a cooling water treatment programme'. This has received some criticism for being a general guide to operating cooling towers rather than focussing specifically on the prevention of legionnaire’s disease. The authors would no doubt argue that maintaining a clean and efficient cooling system is a prerequisite to the successful control of legionella bacteria. However, much of the new text is background information rather than specific guidance.

The new text mentions evaporative air cooling (using evaporation directly or indirectly to cool ventilation air) but then clouds the issue by suggesting that these systems may or may not require notification under the Notification of Cooling Towers and Evaporative Condensers Regulation. The important point that is missed is that these systems should be design and installed with features that minimise the risk of legionnaires disease and should be included in the risk assessment and written scheme with appropriate monitoring and maintenance procedures. However, as they have little in common with cooling towers it would have made more sense to include them in Part 3.

The design, installation and commissioning aspects of cooling towers and associated systems expand on the detail of previous guidance. The chapter on requirements of a cooling water treatment programme actually contain very few requirements or usable guidance other than Table 1.1 entitled 'Typical cooling water desired outcomes' which is overridden by 'The particular desired outcomes and the metrics to be used should be agreed between the system owner/operator and their specialist water treatment service provider'. This is followed by Table 1-2 'Example of how to use water analysis results to predict the risk of fouling', which is not particularly focussed on legionellae.

The situation is further confused by Table 1.9 'Comments and action levels in response to general microbial counts e.g. dip slide results' and Table 1.10 'Comments and action levels in response to legionella analysis results', that are non-negotiable and stick more or less to the previous guidance.

The recommended frequency of routine monitoring is weekly for TVC (Total Viable Counts) and quarterly for legionella (paragraph 1.60) unless there are particular circumstances where more frequent monitoring would be useful (as previous guidance - examples in paragraph 1.126).

The interpretation of the legionella guidance in the of Table 1.2 (3rd row) in respect of 4 samples appears to be a time series but this is not explained.

Overall, the new elements of information and guidance relate to the general operation of the cooling tower to reduce fouling and corrosion but the evaluation of microbiological test results in relation to the acute risk of legionnaires disease has not changed.

Maintenance activity may have to be adjusted to meet the new guidance on fouling though it is likely that contractors following good practice would already comply. Plant operators only need to ensure that their operating and maintenance regime for the cooling towers is sufficiently well documented to meet the requirements of the ACOP, both in terms of written procedures and the recording of tests and inspections.

[edit] Guidance on domestic water systems

HSG 274 Part 2 section 2 provides a more extensive description of domestic hot water systems than the previous guidance. As in the case of cooling systems, the suggestions now include the general design and operation of the system as well as the aspects that are specifically related to the list of legionnaire’s disease e.g. there are now frequent references to compliance with the Water (Water Fittings) Regulations and Water Quality Regulations.

There is an apparent differentiation between the installation and commissioning of small and large developments or systems but these terms are not defined and are inconsistently applied through the document.

A comparison of the specific recommendations HSG 274 and the previous guidance is shown in the following table. Aspects where the new guidance has increased the monitoring or maintenance requirement are highlighted.

Table 2.1 Checklist for hot and cold water systems is more or less equivalent to the old Table 3 Monitoring the temperature control regime but reorganised in terms of service type.

In several cases there are new specific guidelines that could increase maintenance and monitoring. Of particular note are the requirements for increased monitoring of non-sentinel outlets on a rotational basis and monitoring of sub-loop return temperatures in the domestic not water circulation. Some of the others are rather obvious maintenance activities that are not specific to legionnaire’s disease e.g. checking the condition of external insulation and salt levels at the water softener. There are also a couple of things that have apparently been deleted e.g. cleaning the water softener and measuring the inlet temperature to TMV’s (Thermostatic Mixing Valve). It’s not clear whether these were intentional or accidental deletions.

Table 2.2 gives guidance on action to take if legionella is found in the water system. The two action levels (100 to 100 cfu/litre and >1000 cfu/litre) are the same as Table 2 in the previous guidance and the wording is similar.

[edit] Guidance on other risk systems

HSG 274 Part 3 is little more than a list of systems that may be encountered and draws from checklist 3 in the original guidance. There are some additional tasks associated with dental equipment but otherwise the scope and frequency of monitoring and maintenance is the same as previously.

[edit] Conclusions

The revision of the ACOP and guidance in 2013 was an opportunity to update and improve the guidance provided to system operators, risk assessors and duty holders. Unfortunately it was a case of too many cooks with their own agendas with the resulting documents being weighed down by detail that is peripheral to the principal objective of reducing the risk of legionnaire’s disease. As a result, it is sometimes difficult to draw out the important guidance from the general discussion.

Overall, there are few areas where the substantive guidance has significantly changed (the temperature monitoring of hot water loops is one). It certainly does not mean that a risk assessment compiled according to the old guidance is suddenly wrong but it is always important to review any risk assessment and consequent operating and maintenance procedures on a regular basis and particularly when circumstances change or new guidance comes along.

This is a longer version of BSRIA article, ‘HSG 274 Legionnaires' disease, Technical guidance’ published in April 2015. It was written by Reginald Brown, Head of Energy & Environment, BSRIA Sustainable Construction Group. Information is provided for information only and should not be relied on as a means of compliance with legislation. BSRIA cannot be held responsible for any errors or omissions.

--BSRIA

[edit] Find out more

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

Featured articles and news

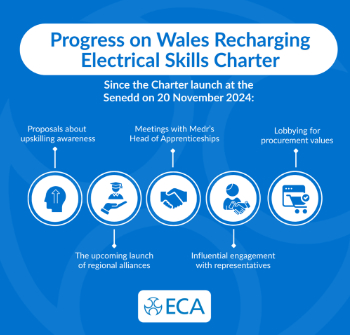

ECA progress on Welsh Recharging Electrical Skills Charter

Working hard to make progress on the ‘asks’ of the Recharging Electrical Skills Charter at the Senedd in Wales.

A brief history from 1890s to 2020s.

CIOB and CORBON combine forces

To elevate professional standards in Nigeria’s construction industry.

Amendment to the GB Energy Bill welcomed by ECA

Move prevents nationally-owned energy company from investing in solar panels produced by modern slavery.

Gregor Harvie argues that AI is state-sanctioned theft of IP.

Heat pumps, vehicle chargers and heating appliances must be sold with smart functionality.

Experimental AI housing target help for councils

Experimental AI could help councils meet housing targets by digitising records.

New-style degrees set for reformed ARB accreditation

Following the ARB Tomorrow's Architects competency outcomes for Architects.

BSRIA Occupant Wellbeing survey BOW

Occupant satisfaction and wellbeing tool inc. physical environment, indoor facilities, functionality and accessibility.

Preserving, waterproofing and decorating buildings.

Many resources for visitors aswell as new features for members.

Using technology to empower communities

The Community data platform; capturing the DNA of a place and fostering participation, for better design.

Heat pump and wind turbine sound calculations for PDRs

MCS publish updated sound calculation standards for permitted development installations.

Homes England creates largest housing-led site in the North

Successful, 34 hectare land acquisition with the residential allocation now completed.

Scottish apprenticeship training proposals

General support although better accountability and transparency is sought.

The history of building regulations

A story of belated action in response to crisis.

Moisture, fire safety and emerging trends in living walls

How wet is your wall?

Current policy explained and newly published consultation by the UK and Welsh Governments.

British architecture 1919–39. Book review.

Conservation of listed prefabs in Moseley.

Energy industry calls for urgent reform.